Before Florida’s deadly condo collapse, one of the Canadians behind the development faced decades of lawsuits and claims of fraud

Dozens died when Champlain Towers South in Surfside, Fla., fell apart this summer.

Globe and Mail

Robyn Doolittle

Adrian Morrow U.S. Correspondent

Uday Rana

Toronto and Surfside, Florida

30 November 2021

Note

This is a very long article describing the career of Toronto based developer. I would have shortened it but I was concerned that the thread would be lost.

—editor Condo Living

Dozens died when Champlain Towers South in Surfside, Fla., fell apart this summer. By then, its Canadian developers were long dead – but hundreds of records tell the story of dubious tactics used to create a property empire from Toronto to Florida.

After years of construction, delays and squabbles with local government, the developers of the Champlain Towers gathered at a ribbon-cutting ceremony to celebrate the project’s completion.

Mitchell Kinzer, who was then the young mayor of Surfside, Fla., still remembers the day well, even 40 years later. The town commissioner, some of the engineers and architects, and a smattering of locals showed up for the dedication. Afterward, a group – including him – was invited up to a penthouse suite owned by one of the developers.

“It was first class luxury. It had these big windows … You could see every marking on the floor of the ocean,” he said. “I literally went home, put on a bathing suit and went swimming. That’s how impressive it was.”

This past June 24, Mr. Kinzer woke up to the sound of helicopters overhead. When he went outside to investigate, neighbours told him about the partial collapse of Champlain Towers South. He thought about that day in the penthouse and later walked three blocks to see for himself.

“The sight of that building, with part of it just literally sheared away, and the giant pile of rubble … It was hard to process that what I was seeing was real,” he said.

Just under 6,000 people live in Surfside. Mr. Kinzer figures there’s not a person who doesn’t have some connection, either directly or through a friend, to one of the 98 people who died.

A federal investigation by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is under way. The original design, construction process, building maintenance, as well as potential environmental and geotechnical issues, are all factors the institute will examine.

And while answers are still likely months or even years away, a myriad of irregularities about the building have come to light since the tragedy.

First, a 2018 consultant’s report surfaced that suggested parts of the high-rise had fallen into disrepair. The document flagged “abundant cracking” in some parking garage columns, beams and walls as well as “major structural damage” to the concrete slab below the entrance drive and pool deck. The report said the original design of the slab was a “major error,” as it was not sloped to allow water runoff.

Expert analysis, and reporting by some U.S. media, has flagged other possible shortcomings with the design and construction of the tower.

Scrutiny has also fallen on the people involved in the project. A confounding number of them appear to have checkered pasts, including an architect who had his licence suspended for incompetence and an engineer who oversaw a potentially deadly design flaw in a different building.

Then there were the developers themselves: Nathan Reiber, Nathan Goldlist, Isadore Goldlist and Roman “Abe” Blankenstein.

All of these men died before the Champlain collapse. But The Globe and Mail has drawn on hundreds of business records, property documents, court files and archived newspaper stories, plus interviews with friends, family and former business partners, to piece together their paths to Surfside, as well as the many problems that plagued the doomed condominium.

Each man immigrated to Canada from Europe and ultimately settled in Toronto. They were scrappy entrepreneurs who struck gold in the housing boom after the Second World War, making small fortunes building the kind of boxy, utilitarian apartment towers that remain ubiquitous in many Canadian cities.

Isadore Goldlist’s brothers ran a poultry shop, but he bucked the family business and became a builder. His cousin, Nathan Goldlist, initially settled in New Jersey on a chicken farm before joining his family in Canada. Mr. Blankenstein and his long-time business partner, Joseph Fialkov, started out as electricians who grew their company, Falco Electric, into a property developer. They went on to build more than a dozen apartment towers. (Mr. Fialkov is listed as a director on companies involved in the Champlain, but it’s not clear whether he was involved in the development at the time.)

But the leader of this group was Mr. Reiber, a gregarious, smooth-talking lawyer, who seemed to live his professional life dancing on the edge of right and wrong. (Members of Mr. Reiber’s immediate family did not respond to interview requests.)

Mr. Reiber permanently relocated to Florida in the late 1970s, shortly before the Canadian government charged him with tax evasion. As he quietly dealt with his legal issues, Mr. Reiber emerged as a philanthropist and fixture of local society. He once hosted a cocktail party on his 80-foot yacht – the Rye-Bar – as part of an AIDS fundraiser organized by Elizabeth Taylor. By 2004, Mr. Reiber and his second wife, Carolee, had amassed an estimated net worth of more than US$43.3-million.

Beneath the glitz, however, a Globe investigation has uncovered a career littered with allegations of deception and unethical practices, including accusations of fraud and misleading sales tactics.

Collectively, the Champlain developers built or managed dozens of buildings in Canada before turning to Surfside, including houses, townhomes, subdivisions, motels, apartment complexes and high-rise condos.

Lawsuits are not unusual in the development world. But little compares to the drama that encircled Mr. Reiber and many of his projects. (In one instance, one of his condos had to be reclad because bricks began falling off the exterior.) To the extent that Mr. Reiber’s character, or any of the developers’ histories, played a role in the tragedy of Champlain Towers is not known and may be impossible for investigators to determine.

Experts consulted by The Globe said it would be unlikely for a developer in Canada or the U.S. to be responsible for a building’s collapse. Developers don’t pour concrete or draft designs. They hire architects and contractors, who are beholden to strict regulations, conservative building codes and inspections. If major errors are made with a design or load calculation, they’re typically revealed during construction, when most collapses occur.

Yet Champlain South fell, decades after it soared into the Florida sky, and no one knows why. This is the story of the controversial man who built it.

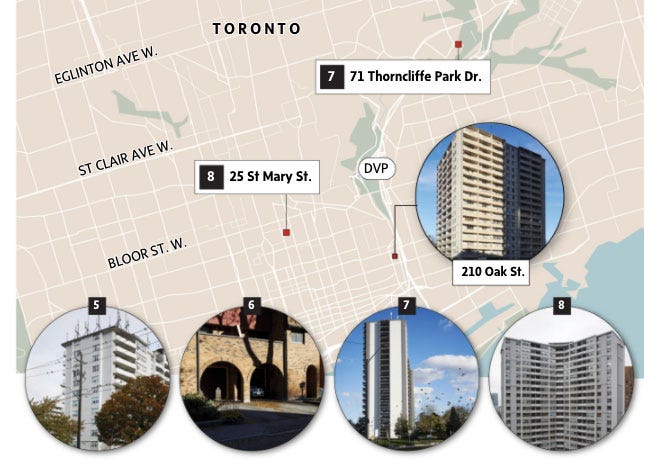

Map: Reiber and company’s Toronto connections

From the 1960s to the 1970s, developer Nathan Reiber and investors who worked with him built more than a dozen Southern Ontario apartment towers and townhouse complexes, mostly in the Toronto area.

When Nathan Reiber died in July, 2014, an obituary in the Miami Herald suggested he had moved to Florida after retiring from a successful legal career. But shortly after his arrival, the writer was told, he took a stroll along West Avenue in Miami Beach and spotted a vacant lot. Inspiration struck and Mr. Reiber discovered a second calling as a builder.

Except this wasn’t true. Mr. Reiber was involved in real estate for almost his entire working life, as a developer, investor, lender and property manager. His portfolio included mortgage businesses, a motel company, subdivisions, townhouses, at least nine apartment buildings and a condo tower – and that’s just in Ontario.

In Florida, he was involved in building at least six condominium towers and part of a subdivision, seven projects to convert existing apartment complexes to condos, co-owned three other apartment complexes, and had ownership stakes in at least three other pieces of land.

Mr. Reiber worked with some of the day’s most prominent Toronto area developers, including Mendel Tenenbaum, George Goldlist at Goldlist Construction (a distant cousin of Isadore and Nathan’s) and New Style Construction.

As for his legal career, this ended in disgrace. Mr. Reiber became a U.S. resident in 1980, around the time he was charged with three offences under Canada’s Income Tax Act. He had been implicated in a coin-laundry skimming scam and was also accused of issuing $120,000 worth of cheques for construction work that was never done, The Hamilton Spectator reported. According to a disciplinary summary from what is now the Law Society of Ontario, Mr. Reiber and others had made “false or deceptive entries” in company record books to avoid their tax exposure. He agreed to resign his law licence rather than be disbarred.

He also eventually pled guilty to tax evasion and paid a $60,000 fine, the Spectator reported.

Mr. Reiber, who was born in Poland and moved to Edmonton with his parents as a child during the Great Depression, graduated law school from the University of Alberta. He was called to the bar in 1953 and within two years, had moved to Toronto with his first wife, Florence.

Toronto in those postwar years was an uninspired place. Apart from a few streets in the core, the skyline consisted of church spires piercing through treetops, overlooking rows of single-family homes. The city was still relatively small. Many neighbourhoods in midtown today were still farmers’ fields.

But Toronto was on the cusp of a major evolution. A thriving economy, new immigration policies and a cultural shift that saw young, unmarried adults living alone for the first time, created a massive demand for affordable “non-family housing” – townhouses and apartment buildings – as it was then called.

The building boom began in the late 1950s, and then took off in the 1960s and 1970s. Some of Canada’s most famous development firms made names for themselves, including Cadillac Fairview, Greenwin and the Tenen Group. Even so, much of Toronto’s postwar stock was built by small-time entrepreneurs. And as a young lawyer, Mr. Reiber saw the opportunity.

Mr. Reiber had partnered with an already well-established barrister named David Newman. The pair rented a modest office for Newman & Reiber above a tailor shop on Spadina Ave. Old classified ads show Mr. Reiber did work such as legal name changes, but by 1958, both lawyers were looking to real estate.

That’s the year they incorporated a side venture, Newrey Holdings, to invest in properties. Mr. Reiber took on builders as clients and then began investing in their projects, which was common at the time.

Many of his early deals also involved a man named Max Citron. Mr. Citron made his money in the stock market and then real estate, said Claire Zur, whose husband, Moshe, worked with Mr. Reiber and Mr. Citron on deals in Florida in the 1970s.

“Max Citron was the one with the money and he got them hooked into real estate,” Ms. Zur said. It was her understanding that Mr. Citron was related to Mr. Reiber’s wife, Florence.

One of Mr. Citron and Mr. Reiber’s early projects involved buying a large stake in two Ontario motel chains, Tops Motor Hotel and Carousel Inn.

In 1965, engineer Alex Tobias sued the chains, alleging Mr. Reiber hired him for numerous jobs, but once the work was done, refused to pay $12,140 worth of invoices – the equivalent of more than $100,000 today.

Under questioning, Mr. Reiber claimed he never had conversations with Mr. Tobias about any work. After Mr. Tobias’s lawyer suggested an outside architect may have been aware of the agreement, the court transcripts stop. Mr. Reiber and the others agreed to settle for almost the full amount.

Just a year later, Mr. Reiber, Mr. Citron and Mr. Newman were sued again in connection with Tops locations in Peterborough and Belleville, this time by some of their partners, Sam Mandle, Charles Wener and Macks Pearlman. The trio alleged that Mr. Reiber, Mr. Citron and Mr. Newman had defrauded them out of at least $64,147 – the equivalent of around half a million dollars today. The case was settled out of court for an unknown amount.

As some of these motel locations began to struggle financially, reams of litigation followed, which exposed other owners, including the involvement of New Style Construction, a major builder run by developers Sam Bojman, Michael Finkelstein and Irving Naiberg.

These names appear alongside Mr. Reiber’s projects throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In Toronto, there’s a cluster of buildings near Bathurst Street and Sheppard Avenue West. Another is at the north end of Regent Park. There’s one on Thorncliffe Park Drive, one off Yonge Street downtown and another tower in London, Ont.

Most share a similar look. They are unfancy rectangles with large balconies, ranging from around 12 to 24 storeys in height. Today, most are still affordable rentals.

“As a kid, all these guys would show up at my house and we’d go to Florida,” said Deborah Bojman, the daughter of Sam Bojman.

She remembers Mr. Reiber as charismatic, funny and someone who commanded attention. Physically he was a large man, tall and broad.

“Nathan was very stylish, the way he dressed. He seemed to have sophisticated taste … he seemed to be polished,” she remembered. “Nathan Reiber was someone who always talked a lot. A good talker. Smooth … he was always very nice to us kids.”

It was with the New Style owners that Mr. Reiber encountered his first public scandal.

In 1966, the group had plans to build a townhouse-apartment complex in Toronto’s west end. They signed options to buy 62 houses and in March, the developers notified about two dozen of those residents the project was going ahead and they had to be out by early June. A number of those residents put down deposits to buy new homes. Others signed long-term leases elsewhere.

But as the closing date approached, some of the residents grew nervous because they hadn’t heard anything else. Their lawyers tried to contact Mr. Reiber – who they understood to be the developer’s lawyer – but he wouldn’t answer the phone. Mr. Reiber was called to appear before the city’s building and development committee to explain.

He was greeted by a room full of tearful and angry residents. Mr. Reiber told the city councillors his “client” – he did not disclose he was also an owner – had decided in May that the project wasn’t financially feasible. He claimed all of the residents’ solicitors had been notified.

“That’s a lie,” shouted resident Stanley Moczulski, The Globe reported at the time.

Mr. Reiber clarified that he told every solicitor who phoned him about the developers’ decision. He denied he had been “hiding or unavailable,” the Toronto Star reported. Then alderman Charles Caccia asked Mr. Reiber why he didn’t think he had a duty to make sure everyone knew about the change. “I’m a solicitor and I have to have one thing in mind and that is the protection of my client. That is my sole duty,” Mr. Reiber said.

In the 1970s, the newly legislated concept of a condominium took off in Toronto. The introduction of rent control and a restructuring of the tax system made rental apartments less appealing to developers. Many, including Mr. Reiber and his partners, switched to condos.

They had initially envisioned Canyon Towers as an apartment building but it registered in 1974 as a condominium. Roughly a decade later, the building’s board hired an outside architect, E. Ronald Hershfield, because the brick facade had begun to fall off.

Mr. Hershfield, 74, says the wrong type of brick had been installed for that type of building and Canada’s winter climate. He designed a cladding system to envelop the structure. “I think they had, as a group, received some kind of a settlement from the developer,” he said.

Asked if he felt the developers may have cut corners, Mr. Hershfield said it’s possible, but not necessarily the case. “It’s not always deliberate. It could have been an honest mistake at the design specification [stage] or a mix-up at the supplier end,” he said.

Speaking generally about many buildings and developers from this era, Mr. Hershfield said the product differed based on the prospective buyer and price point. “These buildings, they’re utilitarian. They meet code. They are acceptable from a safety point of view, but they do not offer anything extra.”

Mr. Reiber and his partners were also sued by the same condo corporation over another matter.

After the building registered, the new board discovered the developers had maintained ownership of the superintendent’s suite. Mr. Reiber and the others offered to sell it to the residents, or lease it for $300 a month. A judge ordered the developers to hand over the suite and the case became a commonly cited precedent in instances in which a condo developer has been accused of breaking the trust of purchasers.

Because of the way property records are maintained in this country, it’s impossible to trace all the buildings Mr. Reiber helped develop, but The Globe located 11 projects in Canada alone. And by 1970, Mr. Reiber was pursuing real estate interests in the Miami area.

Florida was in the midst of its own housing boom, thanks to an influx of immigrants from Cuba and Latin America, changes in federal financing rules that made it easier for developers to build apartment buildings, and the state’s emergence as a vacation hot spot.

Altogether, The Globe identified at least 16 condo and apartment complexes in Florida Mr. Reiber was involved with, from waterfront towers to suburban two-storey walkups.

Although Mr. Reiber had shifted his focus to Florida, in many ways it was not a fresh start. He imported the sort of dodgy business practices of which he’d been accused in Canada.

His first efforts in Florida appear to have begun around 1970, when he registered two companies to develop two different condo projects, including one with Mr. Citron. A few years later, he was part of a Canadian consortium that bought three apartment complexes on the south side of Miami. Mr. Reiber and his partners paid top dollar in a hot real estate market.

Unfortunately for them, the boom ended in 1974 and rental revenues plummeted. The following year, they were forced to sell off one complex, Kendall Village, at a foreclosure auction after missing mortgage and tax payments. An attempt to sell another, Wellington Manor, in 1976, fell apart after the prospective buyers accused the Canadians of refusing to show them proof of the building’s rental revenue, the Miami Herald reported at the time. The buildings sold in 1977 at a loss.

By the end of the 1970s, Mr. Reiber and his partners had their eyes on Surfside, a quiet community of single-family homes with a few modest motels along the beach.

Mr. Reiber bought up parcels of land along Collins Avenue, partnering with Mendel Tenenbaum, and Nathan and Isadore Goldlist. The first site they planned to develop was the former location of a demolished art deco hotel called the Coronado. They dubbed their proposed building Champlain Towers South.

Florida State business records show that 15 companies with overlapping ownership formed the partnership in 1979.

Mr. Reiber appears to have controlled companies that collectively owned 50 per cent of the development. A man named Stephen Gonda is listed as a director alongside Mr. Reiber.

Mr. Gonda, who immigrated from Hungary, was a long-time family friend of Mr. Reiber. His nephew, Lou Gonda, believes his uncle may have sold some real estate at one point, but he was not a particularly wealthy man. (Additional reporting by The Globe supports this assessment.)

Over the coming years, the Canadians ploughed through several obstacles to get the project off the ground.

First was a building moratorium, imposed on Surfside by county officials concerned the town’s sewer system was too small to accommodate new development. Mr. Reiber cut a deal in which he agreed to pay US$200,000, about half the cost of upgrading the system, to get around the moratorium.

The next hurdle was a town council-imposed height restriction that limited buildings to 12 storeys.

“Champlain Towers circumvented the code. Residents did not want to increase any building in Surfside at that time,” recalled Eli Tourgeman, then a councillor. “The town didn’t approve 13 floors, the developers did it and then said it wasn’t really a 13th storey because it’s not really a full floor. But … it wasn’t done according to policy.”

At first, officials ordered the builders to stop construction. But the council, fearing a lawsuit, voted to let the project proceed.

Advertisements at the time said the condos were selling for US$148,000 to US$302,500, about US$450,000 to US$920,000 in today’s dollars. They described generously-sized units: A one-bedroom had 1,600 square feet of space.

But apparently unbeknownst to early residents, Champlain South already contained at least one serious construction flaw. The waterproofing under the deck surrounding the outdoor pool was designed to lie flat, rather than being sloped to drain. This caused water to accumulate, seeping into the concrete slabs in the parking garage below, corroding the rebar and putting hairline cracks in concrete support columns.

Frank Morabito, an engineer who discovered the problem in 2018, laid the blame squarely on the architects and engineers Mr. Reiber’s consortium had hired: William M. Friedman & Associates and Breiterman Jurado & Associates.

Both companies already had erratic pasts by the time they worked on Champlain South in the early 1980s.

William Friedman once had his licence suspended for “gross incompetence,” according to documents from the state’s Board of Architects. In 1965, he was accused of designing faulty sign pylons for two Miami commercial buildings, and a faulty roof for a duplex home.

The board found that Mr. Friedman’s plans for the buildings were not up to code. Mr. Friedman was convicted of professional misconduct and sentenced to a six-month licence suspension.

On at least three occasions in the 1960s, Mr. Friedman was also accused of a practice called “plan stamping,” the file says. This involves an architect rubber-stamping a developer’s plans without ensuring they are sound. Nothing in board documents indicates the outcome of these allegations. Mr. Friedman died in 2018, at the age of 88.

Breiterman Jurado & Associates, meanwhile, was accused of overseeing a potentially deadly design flaw in a different building just a few years before going to work on Champlain. According to a January, 1976, Miami Herald article, a parking garage attached to the new police and fire department headquarters in Coral Gables, Fla., had started to show cracks in the parapet walls on the third and fourth floors just seven months after opening. City officials discovered the builders had used only half the amount of rebar they were supposed to. If a vehicle hit the wall, the city manager said at the time, it could crash through to the street below.

Breiterman Jurado & Associates had been hired to ensure the building followed plans. But Sergio Breiterman, the company’s principal, shrugged off the problem. He told the Herald he could not remember whether he had even bothered to inspect the walls because, he claimed, they were not really “a basic part of the structure like slabs and beams.”

Mr. Breiterman died in 1990. Manuel Jurado, his former business partner, turned down The Globe’s interview requests.

Mr. Reiber himself faced a barrage of lawsuits related to Champlain. Three came from contractors, one from Champlain’s realtor, one from the building next door and one from Isadore Goldist. The details of all of these are unclear because Miami-Dade’s courts destroy their records a few years after cases are closed.

Whatever the difficulties at Champlain, Mr. Reiber and his partners – including Mr. Gonda and sundry Goldlists – immediately made plans for several more beachfront buildings in Surfside. A row of condo towers, many of them almost identical to Champlain, soon populated the beachfront. Mr. Reiber was involved in at least two of these, and Isadore Goldlist was behind three more.

During this time, Mr. Reiber was living large. There was that charity cocktail party on the Rye-Bar in 1988. There was a home on Star Island, a celebrity-filled enclave across the water from Miami Beach. And there were the black-tie balls and galas, including for the ballet and the Miami Art Museum.

In 2004, Mr. Reiber and his second wife, Carolee, listed assets of US$49.3-million and liabilities of just under US$6-million, for a net worth of more than US$43.3-million in a financial statement provided to Ocean Bank as part of financing for a real estate project. In 2005, the couple listed their adjusted gross income as nearly US$2.2-million. To woo real estate agents and financiers for one project in 2006, Mr. Reiber and his partners threw a “Holiday Champagne Yacht Party” aboard a 115-foot boat.

But he was soon headed for yet another legal and financial morass.

In 2009, amid the real estate crash, two banks sued Mr. Reiber and his partners for US$30-million after they allegedly failed to pay back the financing they had received to convert three sprawling, low-rise suburban apartment complexes into condos.

Then, in bankruptcy proceedings related to one complex, the Village at Dadeland in Miami, the bankruptcy trustee accused Mr. Reiber and his partners of improperly funnelling more than US$7.8-million out of the development, leaving it unable to pay its debts.

These accusations were never tested in court. A lawyer for two of Mr. Reiber’s partners said that the trustee made an “abatement agreement” with Mr. Reiber. The court record does not specify details of this agreement.

It was a messy career capstone for a developer who never seemed to stay out of trouble.

At 1:18 a.m. this past June 24, Adriana Sarmiento, a guest at the hotel next door to Champlain South, videoed water pouring from underneath Champlain’s pool into the parking garage below. In the footage, posted to TikTok, chunks of concrete could be seen littering the garage floor. Within minutes, the entire pool deck caved in.

Then, the building began to shake, letting out loud bangs and flashes of light. The centre of Champlain South imploded, a moment captured on surveillance footage from a nearby building. The wing of Champlain closest to the ocean remained upright for a moment, then fell, too. Only the westernmost part of the structure stayed standing, a tangled mass of rebar protruding from apartments cut in half. The implosion took less than 15 seconds.

For the next month, rescuers combed through a rubble pile, itself four-storeys tall, in the rapidly-vanishing hope of finding survivors. Their work was frequently hampered by the sudden thunderstorms typical of South Florida in summer. Ultimately, crews blew up the rest of the building to prevent it crumbling.

Ninety-eight people were killed, including four Canadians. Thirty-five survived in the uncollapsed part of the building. Just four were pulled alive from the rubble, including one who died in hospital.

Philip Zyne, 71, a lawyer who lives in Champlain North, built by the Canadian consortium around the same time as Champlain South, wondered if his home was safe. “They call it the sister building. It has a similar design, architects, engineers, drawings,” he said. “It could be having similar issues.”

Champlain South residents also pointed to other decay in the building in recent years.

Matilde Fainstein, who lived in a ground-floor unit next to the pool deck and was not at home when the building collapsed, sued the condo association in 2015 after she alleged it failed to deal with leaks in her apartment. The case was settled out of court.

Daniel Wagner, her lawyer, told The Globe that the same problem happened again just this past April. A portion of stucco had peeled off the building’s external wall, revealing cracked concrete and rusting rebar below.

Right behind, the concrete support looked like it was blown out and you could see some corroded steel,” said Mr. Wagner, of the firm I Lawyer Up. “The building was in substantial disrepair.”

Allyn Kilsheimer, a veteran Washington-based engineer investigating the collapse for the town of Surfside, said the original design and construction of Champlain South would be the first thing he would look at.

“Our focus is, first, on the original design of the building. Then, our focus is on the materials used in the building, maintenance, then possible outside issues that could have caused something like this,” he said.

He said he would also look at whether adding the penthouse, which wasn’t in the original plan, played a part in the collapse. And Mr. Kilsheimer said he has been inspecting Champlain North to see if any of Champlain South’s problems are present there.

One problem is that much of Champlain North doesn’t appear to have followed the architectural design. Many construction decisions were made on the fly.

“Not everything is built to the drawings. There were not a lot of details on a lot of things – they were worked out while you were building the building,” he said. “For instance, we don’t know who the concrete subcontractor was, or the steel suppliers.”

Whatever the cause, the NIST said earlier this month that its investigation could take more than two years.

Mr. Kilsheimer said he doesn’t know when he will be able to report his findings because the county and the courts have allowed him little access to evidence. He has been allowed only one visit to the collapse site so far, and has not seen any of the debris that was hauled away and put in storage. For the most part, his investigation has involved reviewing the original engineering drawings.

As for the other Surfside buildings constructed by members of the Champlain South consortium, Mr. Kilsheimer says he has not seen anything in Champlain North that indicates it is in “imminent danger of collapse.” But he said the building had commissioned another engineer to do a fuller evaluation. He said he has not been allowed into Champlain East, save for a one-hour tour of the parking garage.

Surfside Mayor Charles Burkett said the town has asked all building older than 30 years to do their 40-year building recertifications early and he believed most were complying. But even so, he worried that without knowing exactly what caused the collapse, it is impossible to be certain the same problem is not present in other buildings.

“How do you know how to diagnose the disease if you don’t know what the disease is, or where it is, or what caused it? And why is it okay to wait years to get that answer?” he said.

He said the town is growing frustrated. “It’s very unclear to me whether we’ll ever get a definitive answer on why that building fell down, and it appears to me that we’ll probably end up with some sort of homogenized answer along the lines of ‘bad design, bad construction, and bad maintenance,’” Mr. Burkett said.

“However, buildings in America just don’t fall down like that. And in my opinion, based upon my conversations with all the experts that I’ve talked to and the hours and hours of time I’ve spent at the site, there is something very, very wrong that happened at that building.”

With research from Stephanie Chambers and Rick Cash

I lived in two of the buildings that are mentioned in this article; one a rental building on Sheppard Avenue West and the condo at 100 Canyon.